By Frances James (1922 – 2019)

This is probably the best known cemetery in Dallas County, maybe Texas! Thousands of vehicles pass by daily since it is on Central Expressway at the intersection of Lemmon Avenue and adjacent to a Wal Mart Center.

Freedmans’ Cemetery was well publicized world wide when the Texas Highway Department now known as the Texas Department of Transportation prepared to start a very costly widening of State Highway 75 through Dallas County. As early as 1990 the Highway Department had begun surveying the area and making plans for the archaeological word that would be necessary to redesign Central Expressway and the crossings at Lemmon Avenue and Hall Streets. TXDOT contacted the Texas Historical Commission and the Dallas County Historical Commission and provided preliminary information. Research started with the deed records and many old maps of the area that noted the five cemeteries along the right-of-way for the Houston and Texas Central Railroad that went through Dallas.

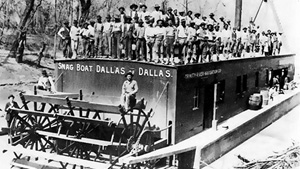

Railroad construction in Texas had been halted for the four years of the Civil War. After the war ended in 1865 it took the companies several years to organize their financial structures and begin building again. The route for the Houston and Texas Central from Houston to Sherman and beyond had been determined before the war but this project stopped at a small town, about half way between Houston and Dallas, called Millican. Building materials, foot and supplies shipped from Houston had to be brought the rest of the way to Dallas by wagons for many years. It was slow and the roads were not always accessible if it rained. The citizens of Dallas had tried using Trinity River for transportation which was not successful and were elated when the rail transportation with the help of Jay Gould and others finally became a reality. When the first HTC train arrived in Dallas in July 1872, all the way from Houston, it was only an engine, eight freight cars, and a single passenger car at the rear. Rail transportation changed the way the City of Dallas would develop.

Most of this area of Dallas County was in the over 4440 acre Grigsby League assigned to John Grigsby by Sam Houston, the President of the Republic of Texas in 1842. The League covered a large section of what would become the City of Dallas in the future. Freedmans Cemetery is in this survey. The first recorded parcel of land for the Freedman cemetery was a one acre tract purchased for $25.00 by Sam Eakins in 1869. By 1884 the Freedman Cemetery Association had been formed and the trustees purchased three more acres. The names of those trustees were A. Wilhite, Frank Read, A. Boyd, F. Watson, A. R. Griggs, S. Pittman and George English.

Two of these men were well known and active in various local civic groups. Sidney Pittman was one of, if not the first, black architects in Dallas and also started a paper that ended his career in Dallas. A. R. Griggs was a local minister. In 1915 a City of Dallas park was named for Reverend Griggs.

In the county on the outskirts of the small area of eight square miles, that was the city limits of Dallas, a black community formed between what is now Lemmon Avenue and Hall Street. This settlement began after the slaves were freed in 1865 and came together looking for other members of their families that might have made it to Dallas. The freed slave population grew faster than the white since this area offered so many opportunities to find a job. There were several other freedmen communities where people could live as squatters. They helped each other while looking for jobs and housing. Stringtown, was another settlement that developed on the north side along the H&TC railroad tracts in the 1870s. The cemetery near this Freedmans town on the north side of Dallas was the focal point for the communities.

Four other cemeteries were started in the same vicinity as Freedmans. Trinity cemetery began in 1868 when the Masonic and Odd Fellow cemetery downtown for whites was running out of space. Trinity was on land adjacent to a five acre site to be used as a pauper cemetery by the city and county of Dallas. The trade of these five acres was a special hand shake deal between Mayor W. L. Cabell and William H. Gaston, and W. H. Thomas, owners of Trinity Cemetery. The three acres purchased by the City as a City cemetery from Mrs. Nancy Turbeville was adjacent to the Masonic Cemetery downtown. Land for the Catholic Cemetery , Calvary, was purchased in 1878 by the Bishop Claude Dubuis of Galveston, as the Dallas Diocese was not established by the Pope until 1903. Temple Emanu El, purchased property in 1884 for a reformed Jewish Cemetery. This area north of the city limits of Dallas was annexed in 1887.

The one acre of land purchased by Mr. Eakins for $25 and the three acres purchased by the trustees were adjacent to the 200 foot right-of-way purchased for the railroad. The cemetery was used by all persons, rich or poor. No records were kept. No plan or design had been made. Most of the burials were not marked with a headstone. Various funerary practices were involved. The number of burials expanded outside the original four acres that had been provided. They protruded into the railroad right-of-way. By the turn of the century, the situation was getting desperate. Shallow graves were dug at night and this was disturbing the other burial sites.

The land purchased by Sam Eakins and the trustees later could not legally expand in any direction. Finally in 1901 the City/County purchased land in South Dallas on Pine Street to provide future burial spaces and tried to close down Freedmans Cemetery, even hiring a guard to prevent burials at night.

In 1907 after thirty-nine years Freedmans Cemetery was officially closed and the newly passed Dallas City Charter of 1907 now had the right to regulate burial grounds when demanded by the public interest or public health.

Meanwhile other black cemeteries were struggling to develop, land for the new City/County Pauper cemetery east of Oakland Cemetery in South Dallas had been purchased in 1901. But due to the restructuring of city government, the deed records and paper work were lost for a few years while ownership was being established. This property also had another problem as there was no adequate road to get to it. Finally on July 26, 1907 the Dallas Times Herald announced that the new cemetery to be named Mt. Auburn was now formally opened. This was six years after the purchase and ten months after Freedmans’ was officially closed.

The original plan was that this six acre site was to be divided with one half for indigent blacks and one half for indigent whites. Not even this intent was followed as determined from pitiful records and personal memories plus a map drawn by the Park Department in 1965. There are Civil War veterans, handmade headstones with Mexican names and a large stone for a freed slave who came to Texas in 1864 and died at 102 years old. There are children of the poor who died during the depression. There is no true pattern here.

Land for the Woodland and Hillside Cemeteries on Hatcher Street had been purchased by John Paul Starks, William B. West and William E. Ewing in 1911. It is believed that several graves of those buried at Freedmans were moved to this new cemetery. Lots were sold for five dollars or ten dollars and those buried were honored with dignified headstones.

So for many years the history of upkeep for Freedmans Cemetery was attempted by a few who would organize, collect some funds, disband or fade away. Most of the original trustees had passed away and no one stepped up to take their place. One or two approached the City to do something, but not much happened. In 1927 a series of quitclaim deeds on a 2.16 acre portion of the property took place and unfortunately the fact that the land had been used as a cemetery was left off the deeds. One-room houses had been built on parts of the property, without plumbing so no digging took place. The land was sold at auction in 1931 to some of the same people who were involved in these deeds. Very questionable transactions are documented.

Finally Emanu El Cemetery purchased the land that touched their property intending to save it for future expansion.

As automobiles, buses and trucks became more numerous the method of transportation by rail declined. The old roads and streets in the vicinity were not adequate to handle all this fast moving traffic. The Texas Highway Department acquired the H&TC Right-of Way in the 1940s to use for a new wide road to be called Central Expressway! This highway was to go all the way to Sherman and Denison! Deed records guaranteed that the highway would be built on the railroad right-of-way that had been acquired by the Houston and Texas Central Railroad in 1872.

By now, in 1958, the original four acres of Freedmans Cemetery was thought to be valuable land so a series of unusual deeds occurred on this land. The Dallas County deed records reveal the signatures on official papers of William Boales and his daughter. Boales had sold the land to the above mentioned Freedman trustees in 1884 and they paid for it as agreed. These 1958 deeds were signed by William Boales and his daughter who would have been over 106 years old by this date. The Crockett Company was the purchaser this time. Two public notaries swore these individuals appeared before them on March 12, 1958. William Boales had died in 1901. The legality of this deed was tenuous at best. The president of the Crockett Company was Ben Carpenter. The Company held the land until in 1965 when it was quitclaimed to the City of Dallas. To add to the confusion this same piece of property was deeded to the City by the North Dallas Memorial Park Association whose membership consisted of the following: M. B. and Lucille Anderson, Lula Mae Anderson, Lemma C. Bright, Ruth Campbell, Harold M., and Sedalia S. Harden, Christabell L Higginbotham, Jane A. and Wright C. King, Ruby N. Stewart, Duane B. and Mollie Lee Mason. Interviews with descendants said they were asked to accept a small amount of money and were paid. This allowed the City to clear the title and accept this gift from the Crockett Company. The Park Department leveled off the land, removed any head stones that remained and provided swings and see-saws for the neighborhood children.

When the Highway Department made preparations for the widening of Central Expressway in the 1990s they expected some archaeology work would be required. The preliminary plan was to re-inter any bodies found in the right-of- way into space already used as a cemetery. This did not happen as the areas that had been selected were found to be occupied – not vacant. After several attempts to find vacant land a large tract ofland adjacent to Freedmans that had houses on it at one time was purchased for an expansion of Freedmans Cemetery. Over fifteen hundred graves were moved into the new site. This entire cemetery project cost over $12,000,000.00 dollars.

Each site as discovered during this survey was carefully marked on maps. Thorough documentation for all this work has been published in two volumes for future research. Each gravesite that was moved out of the right-of-way was carefully placed in an individual box and all buried together on the additional land that had been purchased for this use. There was one piece of a headstone with the name Bluitt on it. There was one headstone that had been overlooked when the site was cleared years ago that was hidden in the honeysuckle along the old fence. This marker is embedded in the wall on the west side of the open space facility.

The black community wanted to be sure that this site would never be disturbed again. A renowned sculptor, David Newton was selected and the Memorial Gate and open space facility was designed. Funding was started in the black community and several times the project was stopped when the funds were depleted. Some of the contractors who worked on the project failed to monitor the jobs closely. Part of the work had to be redone. Finally several white businessmen made generous donations so that the project could be completed.

In 2002 Emanu El Cemetery decided to clear the land they had been holding for expansion and pave the route to their new Mausoleum. To the surprise of the cemetery committee archeology work revealed that although they had been sold the land as vacant, it had many burials already on it. More overflow from Freedmans Cemetery.

This committee started working with the Dallas Park and Recreation Department who maintain Freedmans Cemetery trying to negotiate a swap of land. Duff Street between Emanu El and Central Expressway dead ends behind Emanu El and was just useless. It was not ever going to be needed as a street again. The trade would be that Emanu El would give the city the acres they had planned to use for expansion and the city would give Duff Street to Emanu El. The only expense for the City would be to move the fence surrounding Freedmans to include the graves on the land that had been used as part of Freedmans. Certain staff members in the Park Department could only see this as more acres to keep cleaned up and more grass to mow and are reluctant to accept the trade. These negotiations have been underway for years but it is hoped that in 2009 this trade actually will take place.

Since there were no records kept and all the markers had been removed, the land had been leveled off with fill dirt added where needed, it is impossible to tell where any of the thousands of graves are now. The site is well cared for by the Dallas Park and Recreation Department. There is adequate parking for any event and a Wal-Mart Store is adjacent to the site. The City of Dallas Public Works has done additional work to the sidewalks and the curbs and gutters along Duff Street. The elaborate sculpture and beautiful gates at the entrance this cemetery for those “Known only to God” is now a tourist attraction for the City of Dallas.

Frances James, “Dallas County History – From the Ground Up, Book II,” 2009.