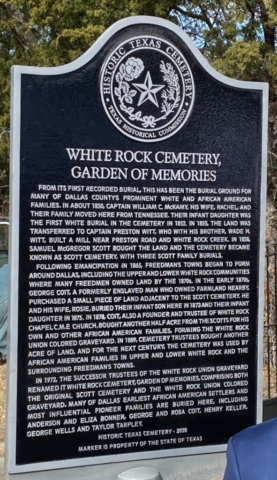

WHITE ROCK CEMETERY GARDEN OF MEMORIES

Historical Narrative Written and Researched by Sheniqua Cummings for the Texas Historical Commission 2019 Undertold Marker Application, Dallas County

I. BACKGROUND

For over 170 years, the land that the White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories now occupies has retained the history of the Upper White Rock community. Aptly named for the White Rock Creek which runs adjacent to it, this 2-acre plot of land, along with the creek, would come to exemplify life and death for the early North Texas settlers and freedmen.

Positioned along the Preston Trail or Old Preston Road in the Far North Dallas/Addison area, the White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories lay in what was the crossroads of the north Texas frontier. The Preston Trail followed what was originally an earlier Native American trade route that evolved in its purpose throughout the years to include serving as a cattle trail and an official Texas military road in 1839 for the Republic of Texas.¹,³ It came to be known by many names, including the Texas Road or Shawnee Trail. The trail extended from present day St. Louis, Missouri to southwestern Texas and was the primary route for immigrants into northern Texas.² Soldiers, pioneers, and cowboys traveled this road from places like, Tennessee and Kentucky until they reached the Red river, and from there on down the Texas Road.³ This area of White Rock Creek was ideal for immigrants because it provided cool water for passersby, frontiersmen and settlers.

Named for its white-hued Austin chalk creek bed9, the area around White Rock Creek became home to Anglo settlers as well as slaves and freedmen alike. Prior to Texas’ annexation to the U.S., the colonists came to the area to settle untouched lands.

II. OVERVIEW

Pre- Civil War

Believed to be the first integrated cemetery in Texas, the land of the present day cemetery has had a long and convoluted history of ownership. The first known owner of the land now known as the White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories was Wade Hampton Witt. Wade H. Witt and his family followed his brother, Preston Witt, to Texas from Illinois in 184512 to take part in the colonization of the new Republic or Texas.6

Preston Witt was one of the first recorded settlers in the Addison area, arriving in 1842 prior to the establishment of Dallas County in March 30, 1846. Trinity Mills Road in north Carrollton is named after the successful steam mill he operated with his brother, Wade Witt and their brother-in-law A. W. Perry”.8 The Dallas County deed⁴ shows that the land part of the Thomas Garvin Survey was granted to Wade H. Witt by Governor E. M. Pease on the 10th of April 1852 through a Peters’ Colony land grant contract⁵, seven years after the Republic of Texas joined the Union in December of 1845.⁶

Wade H. Witt would later become the Trinity Mills Postmaster and then serve as the President of the newly formed Pioneer Association of Dallas County, Texas in 1875. By 1854, the land where the White Rock cemetery now lies was conveyed to John Witt, the father of Preston and Wade Witt, as evidenced on the Nacogdoches Land District map of 1854.7

The oldest known grave in the White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories is that of Margaret McKamy, the infant daughter of William C. and Rachel McKamy, dated 1852.17 In 1851, prior to the original land grant for the Thomas Garvin Survey, Captain William Cooper McKamy moved from Roane County, Tennessee to Texas with his wife Rachel, children and mother. They stopped in Wood County one year, and in 1852 moved to Dallas County, briefly settling on or near the Thomas Garvin Survey. The McKamys eventually moved further west to the Frankford area. The McKamys settled in Carrollton and had at least three other children: William, John T. and Charles. He was very successful in the business of farming and raising stock, and soon accumulated a large land estate of about 3,000 acres.3 William McKamy established the White Rock Masonic Lodge in 1872.

On February 5th, 1855 the land was transferred to Preston Witt from his father, John Witt.10 It was believed that Preston Witt made his home on the property where Preston Road crosses White Rock Creek.6 Preston Witt or Captain Preston Witt was a true pioneer, soldier and rancher. He was born with his twin brother, Pleasant, in Pope County, Illinois in 1819.6 In the summer of 1846, Preston Witt had become legendary following his service in the “Grand Prairie Fight” between the Indians and settlers where he was a part of the self-styled “Minute Men”.6 He later fought in the Mexican War in 1847 where he commanded a Dallas County company of Texas Mounted Volunteers. After returning from battle in Mexico, Preston Witt went into business with his brother, Wade H. Witt, building a mill near Preston Road and White Rock Creek in the late 1840’s.6

Shortly after the mill was built in 1850, the State of Texas sent the land Commissioner, Thomas Ward, to North Texas to issue patents to any of the Peters’ colonists who could prove that they had settled in the area prior to July1st 1848.6 It was during this time that Preston Witt received a certificate redeemable for 640 acres of land. Sam Houston, the first president of the Republic of Texas, granted a colony to W. S. Peters and others with the intention of distributing land to introduce settlers into the north eastern portion of the state, which was then an “uninhabited wilderness”.11 The new settlement was called Peters’ Colony.

It is believed that Preston and Wade Witt either abandoned or sold the mill near White Rock Creek and formed a partnership with Alex W. Perry in 1853 to establish what would be a popular and profitable mill in present-day Carrollton, formally known as the Trinity Grist Mill and Store.6 In 1858, Preston Witt sold the remainder of his land on White Rock Creek and took his family to settle in Parker County.6

On January 26, 1858, Samuel McGregor Scott purchased the land which was a part of the original Thomas Garvin Survey from Preston Witt13. Samuel Scott and his family arrived in Dallas County on January 8th, 1858 from Lynchburg, Virginia.14 It was said that when Samuel Scott and his family arrived with their slaves, the population doubled.15 It was recorded that the Scott family, including their slaves, numbered over two hundred.The Scott Cemetery, as it came to be known, was named for the Scott family. There are three recorded Scott burials on the plot – two infants with unknown dates of death and Josephine Scott, who died at 30 years old in 1878.18

Samuel Scott was born in Virginia, July 26, 1799. He married Camilla W. Scott in 1819 and they had ten children. Both were of Scotch-Irish descent, and Camilla was a member of a distinguished and much respected Virginia family. Samuel enlisted for the War of 1812, but before he reached the front lines, the war had ended. It is noted that the Scott family made the journey to Texas in wagons, brought about forty servants and purchased 800 acres of land.14 The Scotts farmed on a large scale until Samuel’s death in 1878.19

With the influx of settlers from the north, the new landscape was taking shape. By 1850 Dallas County had a population of 2,743 with 207 slaves. The population had tripled to 8,665 by 1860 with 1,074 slaves.21 During the 18 years that Scott owned the land from 1858 to1876 the nation began to go through a social and political transformation and began to prepare for war.

On July 8, 1860, a fire broke out in the square, destroying most of the buildings in the city business district of Dallas. Many residents believed that three slaves caused the fires and they were hanged.21 On February 23, 1861, Texans voted to secede from the Union and joined the Confederate States of America.20 The Civil War commenced shortly afterwards on April 12, 1861. It was during this time that slave holders from other southern states moved to Dallas County with their slaves to avoid attack by Union soldiers.21

Reconstruction

The end of the Civil War brought emancipation for Texas slaves on June 19, 1865. “Freedman’s Towns” began to form around Dallas County as black communities were established in and around the periphery of the city.22 Local historians have documented more than 30 black settlements in early Dallas. 23 Upper and Lower White Rock were examples of such communities.

The Upper and Lower White Rock communities were started as freedman’s towns, settled by former slaves from the nearby Coit, Caruth and Obier plantations, as well as migrants from other states who came to Dallas searching for work.24 They came from plantations in Carrollton, Farmers Branch, Dallas and other nearby areas and established homes for their families all along the northern side of White Rock Creek.

In Upper White Rock the early settlers owned farms along Midway Road, Preston road near Alpha Road, McShann Road and Keller Springs Road – the latter streets bearing the names of the black pioneer farm owners.39 Newly freed slaves purchased more land in far North Dallas, including what became known as Upper and Lower White Rock, than any other area in Dallas County.25 Notable structures on this land today include the Galleria and Medical City with Central Expressway running through the middle of the area.39

Some of the former slaves had crossed the Collin County line into Dallas because ownership of land by blacks was forbidden in Collin County. Henry Keller, Sr., whose name was given to Keller Springs Road; George Wells and his wife, Phyllis Jackson Wells, and Phyllis’ brother, Mose Jackson were among those who had left Collin County and settled in Upper White Rock.25 It’s around this time that we begin to see the first African American burials on the site in the 1870’s, one of which is the Coit Infant in 1875.18

On December 11, 1876, Charles and Louisa Spear purchased 97 acres of the original 640-acre Thomas Garvin Survey from Samuel M. and Camilla Scott.26 Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules showed that Charles Spear had owned land in Dallas County (Precinct No. 4) as early as 1870.27 In Dallas County there was little opposition to land ownership by former slaves, as the whites already owned more land than they could farm without slave labor.25

On July 16, 1878, George Coit purchased 57 and 54/100 acres of the Thomas Garvin Survey from Samuel Scott only a few months before Scott’s death on October 20, 1878.30 This land was purchased primarily for the use of farming. George Coit and his wife, Rosa sold a half acre of land that same year on November 12, 1878 to B.F. Turner, Felix Brigham, William Harris, William Wilkerson and Sam Coit, Trustees of White Rock School House to be used for a school house building site.31 George Coit was a former slave who migrated to Texas from Georgia. George and his wife, Rosa had three sons: George Jr., Alex and Thomas. The land that he was to later purchase with other stockholders was to become White Rock Union Colored Graveyard, which was adjacent to the Scott Cemetery. George Coit was also one of the first trustees of the White Rock C.M.E. Church.

As the former slaves established communities, they bought land and built schools and churches to create a legacy for their families. White Rock Chapel Church was organized in Upper White Rock on November 15, 1884 serving about 28 families.25 It was the first African American church established in Far North Dallas and the first such establishment for African Americans in the North Texas area.33 The first trustees were: Jack and George Coit, B.F. Turner, Felix Bingham and Willie Harris. The Church was located on Celestial Road, between Preston Road and Montfort, beside the small African American burial ground, known then as the Scott Cemetery. The original site was purchased from the plantation owner, Obier, for the price of ten dollars.25 Additional church land was once owned by the Noell family. Nearby White Rock Creek flowed past the only cemetery for blacks in the area.25 In the years to come, White Rock Chapel Church would become inextricably linked to the cemetery.

On November 14, 1888, Charles Spear and his wife Louisa sold a portion of his land from the Thomas Garvin Survey, abstract number 524, to Oceola Payne or “O.P.” Scott, the son of Samuel McGregor and Camilla Payne Scott.28 A few weeks afterwards on December 4, 1888, Charles and Louisa Spear sold another portion of the land to Sam “S.A.” Scales.29 It is here that we first see a reference to an official designation of interment for the land previously purchased by O.P. Scott:

“…said tract purchased by Samuel M. Scott from Preston Witt…crossing White Rock Creek to the beginning and containing 97 and 51/100 acres and is intended to convey all land above described except one square acre deeded by us to O.P. Scott for the purpose of a graveyard”.29

On February 19, 1889, S.A. Scales deeded one acre of land to Giles Armstrong, George Coyt (Coit) and Henry Keller, the Trustees for the White Rock Union Colored Grave Yard.32

“…have granted, bargained, sold and released and by these presents do grant, bargain, sell and release unto the said Giles Armstrong, George Coyt and Henry Keller, Trustees for the White Rock Union Colored Graveyard, and their successor in office, all that tract of land about 11½ miles north of Dallas, Texas, situated on the waters of White Rock Creek, containing one acre of land”.32 It is this document that establishes the formation of the White Rock Union Colored Grave Yard.

For the next century, the cemetery continued to be utilized by the African American members of Upper and Lower White Rock and the surrounding Freedman’s towns. The White Rock Union Colored Grave Yard was supported and maintained by its Stockholders, the White Rock Union Colored Graveyard Association, made up of representatives from most of the churches in the area. On April 17, 1973 the White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories was established, comprising both the original one acre Scott Cemetery and the 1-acre White Rock Union Colored Grave Yard.34 The care of the cemetery has continued with the trustees of the White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories and the cemetery association.

Urbanization

With the increase in the population of Dallas in the 1960’s came growth and expansion of the city. New buildings, apartments and condos were cropping up all over the city throughout the 1970’s to facilitate urban growth.35 The city itself had expanded well beyond its post reconstruction-era boundaries to encompass a sprawling metropolis of shining skyscrapers and multi-million dollar homes on its outskirts. The area immediately surrounding the cemetery was not immune to this growth.

With condos and expensive communities encroaching upon the boundaries of the cemetery, land disputes were certain to occur. The precipice of the ordeal occurred in the fall of 1969 when the gates to the cemetery erected by the cemetery association were padlocked by OKC Corporation. What followed would be a land case like none ever witnessed before or since in Dallas County. The cemetery would become embroiled in what would be the biggest battle of its existence.

OKC Corporation, a large oil, cement and real estate conglomerate started buying land in the Upper White Rock Creek area in 1969. They purchased three acres of land, including, they claimed, the land known as the White Rock Union Colored Grave Yard. Though the families who had ancestors there made regular visits to the cemetery to take care of the graves, OKC Corporation claimed that the cemetery had been abandoned. A temporary restraining order was filed against OKC Corporation in March 1974 by the White Rock Union Graveyard Association and local churches, including White Rock Chapel, Mount Pisgah, Christian Chapel and St. Paul A. M. E. to prevent OKC Corporation from denying access to the cemetery.36

J. O. Allen, Willie Mae Sowell and Minnie Moody and Trustees of White Rock Chapel Church, which became White Rock Chapel Independent Methodist church after the original church moved,36 wanted assurance that their original church site would be preserved and that the pathway from Celestial Road to the cemetery would remain unobstructed, so they took up the fight on August 13, 1975 against OKC Corporation. Two years later, on February 15, 1977 the trustees received a ruling in their favor. Appeals and re-hearings went on between OKC Corporation and the trustees of White Rock Chapel Church until May 30, 1979 when the Texas Supreme Court upheld the original decision in favor of the trustees.36 This was 10 years after the temporary restraining order was first filed.

White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories survived. Unfortunately, that may not be its last battle. Without protection, it may not be able to continue to defend against big land developers. As it sits squarely in the center of prime real estate, it will continue to be a target for urban expansion.

III. SIGNIFICANCE

One of Dallas County’s oldest black cemeteries37, White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories has a rich history. From its first recorded burial in 1852, the site has laid witness to nearly 170 years of North Texas pioneer history. From white settlers to pioneering former slaves, this cemetery is the eternal resting place of many of Dallas County’s most prominent early families.

Notable Interments

The White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories has over 421 known interments.18 As it was the only cemetery for blacks in the area, many of Dallas County’s earliest black settlers and most influential pioneer families, including: Anderson and Eliza Bonner, George and Rosa Coit, Henry Keller, George Wells and Taylor Tarpley, were laid to rest there.

Anderson Bonner was born into slavery in Alabama, most likely in the late 1830’s. He was a farmer and owner of extensive land holdings north of Dallas along white Rock Creek and Cottonwood Branch. He purchased the properties with funds earned from his farm products and houses he leased to sharecroppers. Records indicate that the warranty deed for one of his earliest land purchases, which was over sixty acres, was filed in Dallas County on August 10, 1874. He married Eliza and they had nine children.38

According to the 1870 United States Census40, Bonner’s personal financial worth was valued at $275. He eventually amassed nearly 2,000 acres of land, located mostly along White Rock Creek and surrounding areas in what is known today as North Dallas and Richardson.38 Anderson Bonner died in 1920. A park has been named in his honor on the west side of Medical City Dallas where his farm land used to be.

George Coit was a true pioneer of the Upper White Rock settlement, helping to build the community. He was one of the first trustees of the White Rock Chapel Methodist Church. The church was organized after a meeting at Coit’s home.25 On November 12, 1878, George Coit and his wife Rosa deeded land to B.F. Turner, Felix Bingham, William Harris, William Wilkerson and Jack Coit to build a school in the community. Coit was also one of the original trustees for the White Rock Union Colored Grave Yard. Coit, along with Henry Keller and Giles Armstrong were deeded land for the cemetery on February 19, 1889. He died January 17, 1903.

Henry Keller was born into slavery in 1817 on a plantation in Greenville, Tennessee. He moved to Texas with his wife Mary Jane Reed after emancipation and settled on a farm in Collin County where they raised ten children. When they reached their first milestone, they purchased a farm and moved to Dallas County where they settled in Addison, the area that is now called Far North Dallas.38

There was an everlasting running spring on his farm that supplied water for him and many of his fellow farmers who needed water at no cost. The farm was located on a farm road which later was named Keller Springs Road in his honor.38

His land ownership continued to grow and he soon acquired several other parcels of farm land in the general area which was known as Upper White Rock. He became one of the larger black land owners and farmers in Dallas County. His holdings totaled 640 acres of land. He lived on his original Dallas County farm until his death in 1911 at the age of 94.38

Taylor Anderson Tarpley was born in Wiley, Texas on August 1, 1865. He and his mother, Anne Turner, moved to Northwest Dallas County and settled in Addison, Texas. His mother purchased a large farm on Dooley Road, now Midway and Keller Springs Road. Taylor met and married Mary Jane Coit on January 7, 1886 and they had fifteen children by 1918. The young father bought a 106-acre farm to raise his family.38

As one of the original organizers of the White Rock Methodist Church, Taylor and Mary were hard working people and proud of their family. They instilled in their children early in life the values of responsibility. This was evident when the Tarpley family was recognized as one of the largest cotton farmers in the area.38 Taylor and Mary Jane insisted on their children getting an education, as many of them went on to receive college degrees. Taylor Tarpley died on October 19, 1938 and his wife, Mary Jane died in 1937.

A prominent figure in the nearby Alpha community, Reverend Elkanah Colombus “E.C.” Bramblitt, a white Baptist minister and his wife, Mary Elizabeth Wade Bramblitt (1842-1893) along with a host of other relatives are also buried in White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories. Elkanah Bramblitt was born in Campbell County,Virginia in 1840 and came to Texas with his parents in 1859. Bramblitt engaged in various occupations which included cattle driver, farmer, school teacher and minister.42 He was the Postmaster in Alpha in 1894.41 Ironically, Elkanah Bramblitt served as a Confederate soldier in Co. E. 18th Texas Calvary in the Civil War, and was buried in what would later be called the White Rock Colored Union Cemetery. He lived in Texas for 76 years until his death in 1936.

Other prominent early Upper White Rock Settlement pioneer families and large land owners from the area resting in White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories include: Taylor and Laura Turner Family, George and Phyllis Wells Family and Isaac and Florence Barton Family as well as many other influential families from the area.38

The Next Chapter

Completely obscured by the surrounding apartment complexes and condominiums, there is real concern that the cemetery could be absorbed and developed by the neighboring property owners or developers waiting to acquire the land. Regular visits by family members and descendants of the interred insure that the cemetery and its residents will not be forgotten; they bring life to its gates and relevance to its existence. Burials are still occurring at the cemetery, the last one was as recent as 2017.

Upkeep of the cemetery is handled by the cemetery association. The White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories, Inc. is a non-profit cemetery association made up of the descendants of early African American pioneers of the Upper White Rock community. They have been meeting annually on the grounds of the cemetery for over 30 years to give honor to their ancestors and to preserve the legacy of the Upper White Rock community. Oral histories and family photos are shared by the surviving family members, keeping the memories of their ancestors alive.

Having a Texas Historical Marker will honor the lives and contributions of the early pioneers of the Upper White Rock Settlement and allow their history and achievements to be shared with those outside of the community. It would commemorate the sacrifices of those who built churches, schools, businesses, owned land and broke barriers with their boldness during a time in our nation’s history when it was a difficult existence for people of color.

History has accepted that after Emancipation blacks were perpetually poor, uneducated and landless. But, pioneers like Anderson Bonner, George Coit, Henry Keller, George Wells and Taylor Tarpley defied those perceptions and achieved economic equality. A stunning achievement during that time, perhaps this rapid advancement motivated the enactment of Jim Crow laws during this time.

Finally, White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories, mostly composed of African Americans who were active members of their North Texas farming communities, is the resting place for a strong , self-sufficient community of people who were exceptional, especially during that time period and in that region of the country. They deserve to have their stories of triumph and struggle told and their sacred, hallowed ground safeguarded against the ravishes of urbanization. With its rich and distinctive history, the White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories is a hidden treasure in Dallas County and worthy to be preserved and designated as a historic Texas cemetery.

IV. DOCUMENTATION

1 Gard, Wayne. The Chisholm Trail. Norman: Univ. of Okla. Pr.; 1954.pg. 296

2 Hannaford, Jean T. Handbook of Texas Online. | Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/exo03. Published June 15, 2010. Accessed April 14, 2019.

3 History. Frankford Preservation Foundation. http://frankfordpreservationfoundation.org/history/. Accessed April 13, 2019.

4 Dallas County Deed Records, Vol. 34: 331-334.

5 Wade, Harry E. PETERS, WILLIAM SMALLING. The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fpe65. Published June 15, 2010. Accessed April 14, 2019.

6 Dallas County Heritage Society. Legacies: A History Journal for Dallas and North Central Texas, Volume 11, Number 2, Fall, 1999, periodical, 1999.pp. 6-12. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth35103/m1/9/?q=%22wade%20h.%20witt%22. Accessed April 14, 2019. University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu. crediting Dallas Historical Society.

7 Swindells, H.J. A Map of That Part of Dallas County Lying in Nacogdoches Land District. The Portal to Texas History. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth89117/m1/1/zoom/?resolution=3&lat=5431.51643066935&lon=3838.4639719393786. Published April 2, 2010. Accessed April 14, 2019.

8 History of Addison. Addison Economic Development. https://addisontexas.net/econ-dev/history-addison. Accessed April 13, 2019.

9 The Handbook of Texas Online. WHITE ROCK CREEK. | Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/rbw74. Published June 15, 2010. Accessed April 18, 2019.

10 Texas General Land Office, “Land Grant Search,” digital images, General Land Office Record entry for Witt, Preston, Dallas Co., TX, no. 1131.

11 de Cordova. South-Western American (Austin, Tex.), Vol. 3, No. 36, Ed. 1, Wednesday, February 18, 1852. The Portal to Texas History. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth79717. Published February 21, 2010. Accessed April 23, 2019.

12 Group GTH. Pioneers of Dallas – History of Dallas County, Texas. http://genealogytrails.com/tex/prairieslakes/dallas/pioneersofdallas.htm. Accessed April 24, 2019.

13 Dallas County Deed Records, Vol. F: 307.

14 Memorial and Biographical History of Dallas County, Texas, book, 1892. The Portal to Texas History. http://www.texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/. Accessed April 24, 2019.

15 James, Francis. WHITE ROCK CREEK, 1910 Before It Was a Lake The… Dallas Gateway. https://dallasgateway.com/white-rock-creek-1910-before-it-was-a-lake-the/. Published January 22, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

16 Jackson, George. Sixty Years In Texas. Dallas, TX: Wilkinson Printing Co.; 1908. pp. 138-139.

17 Conger, W.R. Old Cemeteries of Dallas. Vol 1.; 1981. p.64.

18 Keaton, Dr. George. White Rock Garden of Memories Complete Cemetery Survey. USGenWeb Archives – census wills deeds genealogy. http://files.usgwarchives.net/tx/dallas/cemeteries/whiterock.txt. Accessed May 4, 2019.

19 Harvey, Doug. Four Portraits of Early Lynchburgers Restored and on Exhibition. Google Groups. https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/cvamuseums/uIvx2FU7Y64. Accessed May 4, 2019.

20 The African American Story | Texas State History Museum. The African American Story | Texas State History Museum. https://www.thestoryoftexas.com/discover/campfire-stories/african-americans. Accessed May 4, 2019.

21 Maxwell, Lisa C. DALLAS COUNTY. The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hcd02. Published June 12, 2010. Accessed May 5, 2019.

Hazel, Michael V., McElhaney, Jackie. DALLAS, TX. The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hdd01. Published June 12, 2010. Accessed May 5, 2019.

23 Allen, Leona. Mapping a heritage: Records, oral history show blacks’ huge role in shaping Dallas. The Dallas Morning News. February 5, 1995.

24 Dillon, David. On Hallowed Ground: How Dallas’ oldest black church battled the developers, and won. And lost. D Magazine. https://www.dmagazine.com/publications/d-magazine/1980/february/on-hallowed-ground/. Published February 1980. Accessed May 5, 2019.

25 McKnight, Dr. Mamie L. African American Families and Settlements of Dallas: on the inside Looking out: Exhibition, Family Memoirs, Personality Profiles and Community Essays. Dallas, TX: Black Dallas Remembered; 1990. pp. 46-47.

26 Dallas County Deed Records, Vol. 34:32.

27 Ancestry.com U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880[database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Charles Speer; https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&db=NonPopCensus&h=3535050. Accessed May 9, 2019.

28 Dallas County Deed Records, Vol. 100: 124-125.

29 Dallas County Deed Records, Vol. 98: 608.

30 Dallas County Deed Records, Vol. 98: 608.

31 Dallas County Deed Records, Vol. 39: 536.

32 Dallas County Deed Records, Vol. 102: 219-220.

33 Christian Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal Church. History. CCTOF. https://www.cctof.org/church-history. Accessed May 16, 2019.

34 The State of Texas. Articles of Incorporation: White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories, Inc. Secretary of State; April 17, 1973.

35 United States Census Bureau. Dallas population in: 1880-1990. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

36 Dillon, David. On Hallowed Ground: How Dallas’ oldest black church battled the developers, and won. And lost. D Magazine. http://www.dmagazine.com/publications/d-magazine/1980/february/on-hallowed-ground/. Published February 1980. Accessed May 19, 2019.

37 Bogan, Christopher. Time capsule: Black cemetery endures amid bustle of N. Dallas. Dallas Times Herald. January 30, 1984:1-9.

38 McKnight, Dr. Mamie L. First African American Families of Dallas: Creative Survival. Vol 1. Black Dallas Remembered Steering Committee; 1987.

39 Partee McMillan, Eva. Upper and Lower White Rock- Little Egypt/Fields’. Annual White Rock Cemetery Garden of Memories, Inc. Memorial Day Meeting.

40 1870 United States Federal Census; Census Place: Precinct 4, Dallas, Texas; Roll: M593_1581; Page: 381B; Family History Library Film: 553080.

41 Wheat, Jim. Postmasters and Post Offices of Texas, 1846 – 1930. http://sites.rootsweb.com/~txpost/postmasterindex.html. Accessed May 5, 2019.

42 Martin, W.L. The Carrollton Chronicle. Carrollton, Texas, Vol.32, No. 11, Ed. 1, Friday, January 24, 1936; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth728746/m1/4/: accessed May 2, 2019), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu;.

Photos from Historical Marker Dedication: