The story given here is based on Benjamin J. Prigmore’s own account of his life recorded in the Dallas Morning News, June 7, 1891 in a story written by Cliff D. Cates entitled “Old Pioneers of Texas.” Benjamin J. Prigmore (1830- 1901) was the son of Kentucky native Joseph Prigmore (1807-ca. 1862). Joseph and his family had moved first to Missouri, where Benjamin was born in 1830. In 1844 they set off with other settlers for the Republic of Texas. Benjamin served in the Mexican-American War and then in the Civil War. He received a grant of land in 1866 after his service in the Civil War. His property was bounded by Abrams Road on the west, Forest Lane on the south, Audelia Road on the east, and a line just south of Richland College on the north, roughly following the line of Chimney Hill Lane.

Ted A. Campbell, Associate professor of Church History, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas

The following is his account as it was given in the Dallas Morning News:

When we were moving to Texas we stopped on the East Fork of the Trinity several days to rest. There were some eighteen or twenty immigrant wagons along, and we were a pretty jolly crowd. The fourth day of July found us here in camp, and we thought we ought to celebrate our great national birthday; so we had the biggest sort of a dance upon the green grass of the prairie. The fattest yearling in the herd of cattle was killed and barbecued; and perhaps no festive occasion was ever more enjoyed than that 4th of July was by us – a little band of pioneers on this, the Texas frontier, at that time.

After leaving our East Fork camp we all went west into what is now Denton county and camped two weeks on Elm Fork. You see, the whole of this fine prairie country was before us to select from, and we wanted to take a good look before finally making choice of a section of land. It all looked so rich and green and beautiful that it rather bewildered the heads of families to make a selection.

While we were camped on Elm Fork the Indians slipped in one night and drove off thirty mules belonging to our crowd of pioneers. Father’s loss was especially heavy in this raid, as six of the mules were his, and were all he had. The Indians also killed one of our two milch [milk] cows, leaving us with only one yoke of oxen, one cow and two calves to start a Texas farm with!

No one knew anything of the matter until next morning, so sly and noiseless had the red thieves been. The cow they killed was shot through with an arrow, and we found several arrows lying beside her, one of which was bloody from one end to the other. They also cut out small portions of each hind quarter, leaving most of the carcasses there.

About thirty men of our crowd went in pursuit of the Indians and were gone nearly a week, but did not overtake them. In fact, they followed them so far into the northwest that they were afraid to go further, as the Indians were known to be in strong force in that direction.

On the very night these pursuers got back to camp, I remember that some of their horses were stolen while they were eating supper—some half a dozen, if I remember rightly.

About this time (1844) Cedar Springs was the largest village in this section, and an effort was made to establish the county seat there. Dallas, then a very small village indeed, and also Hord’s Ridge (now Oak Cliff) were the other contestants. John Neely Bryan, known as “the father of Dallas,” donated a lot of ground for county purposes and secured the location of the county seat, and Dallas won her first prize. In August or September we moved down here and built us a log cabin. With a yoke of oxen as our only plow animals we scratched up two acres of ground, using a little old shovel plow, with a jumping coulter in the beam. That fall, after cross-breaking, or rather cross-scratching this patch, father sowed wheat on it—one bushel per acre. We then went to work making rails in Ten-Mile bottom, and by spring had thirty acres under fence. The fence was the old-fashioned worm fence, and about seven to eight rails high. There was but little stock here then, and what little there was had such an abundance of the finest pasturage outside that they had no temptation to break into the cornfield. By corn planting time in 1845 we had fifteen or sixteen acres of land ready, all of which we put in corn. That spring we thrashed out about twenty-four bushels of wheat from our two acres of half-broken sod. We also made a first-rate corn crop—some 200 bushels—most of which father sold to immigrants that fall and winter at $1 per bushel. We had neither horses nor hogs then and had need for but little corn ourselves.

During the spring of 1845 we had another serious loss—one of our two oxen died. This left us with one lone ox with which to make a crop. I was the plowboy and I guided my ox with a line tied to his horns. Of course plowing with a single ox was slow work, but with us it was that or no crops, and I laid that crop by with that one steer.

In the fall of 1845 father went back to Missouri and bought two horses and a mule. We were then very well outfitted with plow stock.

During the winter of 1845-46, I believe it was, Uncle Jackie (Judge) Thomas, who lived across White Rock creek, with two or three of his neighbors, went down into Nacogdoches county and bought a herd of hogs, which they drove to Dallas county. Father bought several of these hogs, and in a year or two we, and the neighbor–hood generally, had plenty of bacon, which was the first we had since we got to Texas. You may be sure we enjoyed it, too, for one gets tired of wild meat when nothing else is to be had.

In ’46, father, myself, and several neighbors went down to about where Haught’s store is now, and we killed a buffalo—about the last one, I think, that was killed west of the Trinity.

Wheat was our loading crop before the war, and crops were uniformly good wherever the land was properly prepared. I have seen good crops made without any previous breaking of the land whatever, but, of course, such cases were not very common. I remember old Uncle Ben Hunter, who used to live on Whiterock, once sowed wheat where his corn grew the previous year, without breaking the land at all. The land was so overrun with wild sunflower seeds that the old man had to take his sack of wheat upon a horse and sow it while riding. He then hitched two yoke of steers to a heavy brush and dragged it over the ground. Nothing else was done. A drizzly spell set in, the wheat came up, grew out nicely, and made twenty-five bushels per acre. I once raised a fine crop of oats in this manner, but it was never a reliable plan. The conditions necessary to its success, was a damp spell of weather immediately or very soon after the grain was sown, in order to sprout it and cause it to take root. Once fairly rooted, it was pretty sure to make a good crop.

When I was about 17, one day I went down to Dallas—it was in the summer of 1847—and there I met a man named Kinzie, who was raising a company of rangers for the frontier service, he said. He was from Fannin county, and had enlisted about thirty men up there. He wanted some sixty-five more. I enlisted into his company, together with a number of other young men from this section, among whom I now recall to mind: Sloan and Bill Jackson, Jesse Cox, Stepha and John McCommas, Lige and Chris Carter, John and Aleck Thomas, John Daniels, Jim Barton, * Chinault, George Mounts, and James Vance.

In three or four days we rendezvoused at Cedar Springs, camped there one night, and next day started for Austin. We were there formally mustered into service, our names recorded and our horses valued. We were then marched down to San Antonio, where our colonel, Jack Hayes, told us that he had orders to take five of his ten companies to Mexico. The other five were to go out on the northwestern frontier. This was not what I calculated on when I enlisted, but, as the Mexican war was then in full blast, I think our boys liked the idea of a chance to go down to the land of Montezuma rather than hunting the red Bedouins on our northwestern borders. Lots were cast to see which of our ten companies should go to Mexico, and it fell to Capt. Kinzie’s company for one; so we were soon on the march for the seat of war.

The following spring (1848), after having been mustered out of service at Vera Cruz, we set sail for home. Here we sold our horses for a mere song.

I have not yet drawn any pension as a Mexican war veteran as I am not quite 62, the necessary age to entitle me to a pension from Uncle Sam’s treasury.

At the beginning of the late war I joined Capt. Allen Heard’s company, Col. Nat M. Burford’s regiment, Parson’s brigade. I served in the states of Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri and the Indian territory.

Since the war I have raised cotton mostly, but do not find it as profitable as wheat used to be before the war.

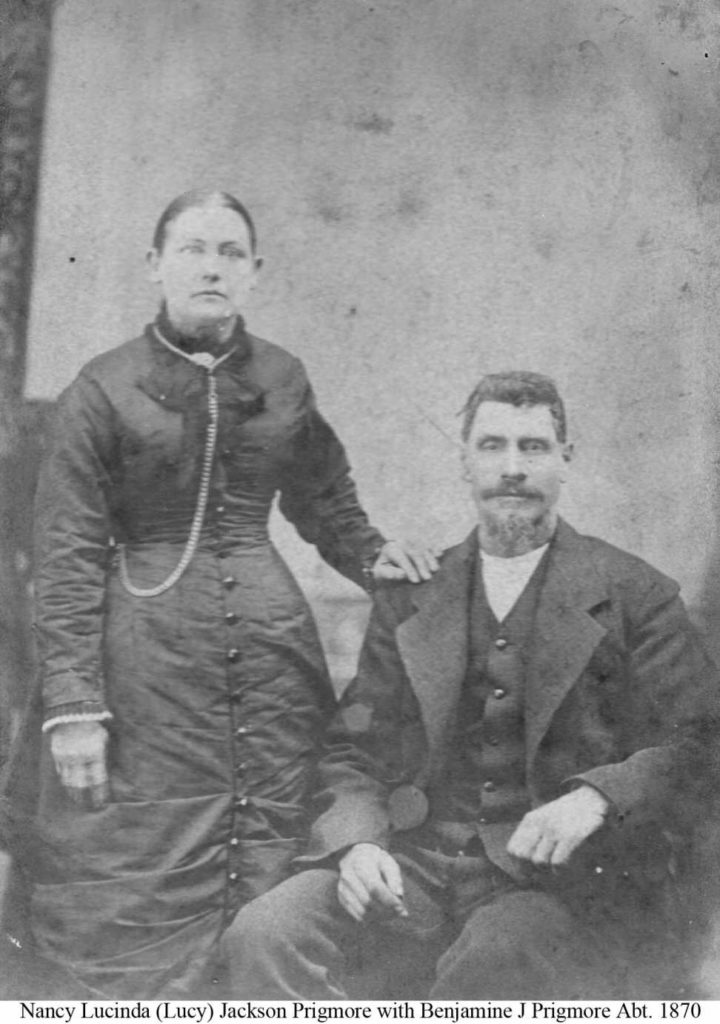

I was married to Miss Lucy Jackson Feb. 8, 1833 [1853]. My wife’s father was also an early pioneer here and lived in this neighbor[hood]. We have raised six children, five of whom are still living and settled mostly near by. Our little Liza was killed in a cyclone when 10 years of age. This sad event occurred May 26, 1867.

Benjamin J. and Nancy Lucinda Jackson Prigmore, 1870.